Anwar Shaikh on Islamic terror

A review on 'Islam & Terrorism'

by Anwar Shaikh (2004)

19 Dec, 2006

As a young Muslim in Lahore, Anwar Shaikh took part in the Partition violence against Sikhs and Hindus. Terrorizing the non-Muslims seemed like the right and natural thing to do for a Pakistani. But after settling in Britain and establishing himself as a successful businessman, he developed second thoughts about his native religion. He started published a periodical for critical discussion of Islam, Liberty , in both English and Urdu, and a series of books on the relation between Islam and topics such as nationalism, violence and sexuality. His demythologising observations about the Prophet and the Quran caused considerable anguish among Britain-based Muslims, especially when the clerics they consulted failed to come up with a reassuring refutation. In the 1990s, he had the honour of being targeted by a number of Pakistani clerics with dire fatwas, finding him guilty of apostasy and insulting the Prophet but mercifully confining the implied death sentence to the jurisdiction of properly constituted Islamic states. He ought to be safe as long as he doesn't travel to an Islamic state.

In this book, Anwar Shaikh sets out to discover and reveal the scriptural and historical roots of Islam's current involvement with terrorism. The question has been occupying the minds of some Indian scholars for decades, but after recent Islamic terror attacks on Western interests, it seems that it is at last being taken seriously by Western audiences, politicians and scholars. Many of them are no longer prepared to swallow the easy answer that terrorism is un-Islamic and that it is only advertised as an Islamic Holy War by misguided individuals unrepresentative of true Islam.

All those people who say that acts of terror such as those on 11 September 2001 are un-Islamic, should tell us on what grounds an Islamic court could sentence an Osama bin Laden. The basis of Islamic law is the Quran along with the sayings and precedent conduct of the Prophet. So, can an Islamic terrorist cite the authority of the Quran and the Prophet in his justification, or can these sources be invoked to the opposite effect?

The answer, Mr. Sheikh argues, is quite straightforward: Mohammed himself was a terrorist, the most authoritative precedent for contemporary Islamic terrorists. To prove his point, he presents long lists of quotations from the Quran, the better-known Hadith (traditions of the Prophet) and also some lesser-known Hadith. In this respect, his book is a treasure-trove of first-hand data on the foundations of Islam and its doctrine of Holy War ( Jihad ).

Numerous canonical statements affirm that the Mujahid or Holy Warrior undoubtedly counts as the best among Muslims, e.g.: “Acting as Allah's soldier for one night in a battlefield is superior to saying prayers at home for 2,000 years.” (from Ibn-e-Majah , vol.2, p.162) Or: “Leaving for Jihad in the way of Allah in the morning or evening will merit a reward better than the world and all that is in it.” (from Muslim , 4639) Jihad, while not a duty for every individual Muslim, is a duty on the Muslim community as a whole until the whole world has become part of the Islamic empire.

The cult of martyrdom is an intrinsic part of the doctrine of jihad: the martyr “will desire to return to this world and be killed ten times for the sake of the great honour that has been bestowed upon him.” (Muslim 4635) And from Allah's own mouth: “Count not those who were slain in God's way as dead, but rather living with their Lord, by Him provided, rejoicing in the bounty that God has given them.” (Quran 3:163) Contrary to a recent tongue-in-cheek theory which reduces the heavenly reward for the fallen Mujahid from 72 maidens to mere grapes on the basis of some Arabic-Aramaic homonymy, a number of Prophetic sayings, in varied wordings mostly not susceptible to this cute Aramaic interpretation, confirm the traditional belief that “the martyr is dressed in radiant robes of faith, he is married to houris (the paradisiac virgins)” etc. (Ibn-e-Majah, vol.2, p.174) This confirms that the suicide terrorists were not acting against Islamic tenets, as some soft-brained would-be experts in the media have claimed. On the contrary, to sacrifice one's life in a jihadic operation against the unbelievers is the most glorious thing a Muslim can do.

In Jihad, it is perfectly permitted to deceive the unbelievers and subject them to terror. Anwar Sheikh provides all the scriptural references plus many precedents from history, which we cannot reproduce here. Suffice it to say there is ample evidence that Islam permits, and that by his personal example or by that of the men under his command, Mohammed has given permission for abduction, extortion, rape of hostages, mass-murder of prisoners, assassinations of enemies and dissidents, breaking of the conventions of civilized warfare, breaking of treaties, and suicide missions. From Osama bin Laden to the murderers of children in Beslan, North Ossetia, the Islamic terrorists are faithful followers of the Prophet.

For all his grim discoveries about the religion of the Muslims, Sheikh is not anti-Muslim: “I was not only born and bred as a Muslim but also fought grimly for the glory of Islam. Even today, my loved ones are Muslim. There is no way I can be anti-Muslim.” (p.306) Being a European outsider to Islam, I always get nasty replies when I say that “the problem is not Muslims, the problem is Islam”; but here you have it from the horse's mouth. It is perfectly possible to retain warm feelings for Muslims yet leave Islam and even criticize Islam.

He continues with some practical advice to Muslims. Setting an example in his own life, he is showing them the way to integration in non-Muslim societies: “I am a citizen of Great Britain, therefore I have a legal and moral obligation to live like other Britons and raise my children as British citizens, who are free to practise any religion they like.” (p.306) This is admittedly a difficult thing to do for the believing Muslim, for the practical core of Islam is not some theological doctrine but the observance of Islamic law, preferably under an Islamic polity but otherwise even in a non-Islamic society. The idea of allowing their children the freedom to choose their own religion, i.e. to choose against Islam and for an allegedly false religion, is abhorrent to most believers. Yet, it is what they have to do if they want to integrate into Western (c.q. Hindu) society.

Unfortunately, Shaikh finds that the number of Muslims ignoring this common-sense rule has crossed a critical threshold to a point where it negatively affects not only Muslim-non-Muslim coexistence, but even the non-Muslim host society itself: “The Muslims in this country have not fully appreciated the hospitality that they have received. (…) It is no crime to be a Muslim in this country but it is a crime to be a terrorist because terrorism has demolished many of those civil liberties for which the West has worked for a long time and given tremendous sacrifices to gain them. Now, they have created such conditions that safety is becoming impossible without identity cards, emergency laws which authorise imprisonment without a trial”, etc. (p.307)

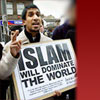

Remember the good old days when the bobbies, Britain's police constables, did their rounds without carrying guns? It cannot honestly be denied that the behaviour of an ever-increasing number of young Pakistanis has contributed decisively to the sad discarding of this glorious tradition. Every non-brainwashed European can confirm that an influx of entire Muslim communities (as opposed to individuals or single families, who tend to blend in like most isolated immigrants do) has created a new set of problems for their societies. The larger these Islamic islands in Western society become, the less willingness they show to adapt, and the more they insist on maintaining or restoring Islamic mores and laws within their communities and ultimately in society as a whole.

The one silver lining to the dark cloud of Islamic terrorism is that it alerts non-Muslim societies to the specificity of the problems which Islam poses. Westerners often feel guilty of xenophobia, “fear of what is strange or foreign”, when they criticize Islam. But the problem of Islam is not one of strangeness or foreign origin, as will readily become clear when you compare it with Buddhism. In Western culture, Buddhism is even stranger than Islam, which shares certain common roots with Christianity, yet people find Tibetans in their native dress colourful rather than threatening. There are no Buddhist gangs attacking peaceful citizens, nor are there Buddhist associations making separatist political demands such as the right to observe a separate law system. Buddhism may be strange, but informed people will agree that it is an enrichment to our society. Islam is less strange, yet its enriching contributions are unclear while its nuisance value is all too palpable. The stark reality of Islamic terrorism blows away the fog of doubt and timidity hitherto surrounding the painful question of how to evaluate Islam.