Review on 'Why I am not a Muslims'

21 Dec, 2006

Why I Am Not a Muslim

by Ibn Warraq

Prometheus, 1995. 402 pp. $25.95

Amherst, New York

In March 1989, shortly after Ayatollah Khomeini issued his decree

sentencing Salman Rushdie to death for his novel The Satanic Verses,

London's Observer newspaper published an anonymous letter from

Pakistan. In it, the writer, a Muslim who did not give his name,

stated that "Salman Rushdie speaks for me." He then explained:

mine is a voice that has not yet found expression in newspaper

columns. It is the voice of those who are born Muslims but wish to

recant in adulthood, yet are not permitted to on pain of death.

Someone who does not live in an Islamic society cannot imagine the

sanctions, both self-imposed and external, that militate against

expressing religious disbelief. "I don't believe in God" is an

impossible public utterance even among family and friends. . . . So

we hold our tongues, those of us who doubt.

"Ibn Warraq" has decided no longer to hold his tongue. Identified

only as a man who grew up in a country now called an Islamic

republic, presently living and teaching in Ohio, the Khomeini decree

so outraged him that he wrote a book that transcends The Satanic

Verses in terms of sacrilege. Where Rushdie offered elusive critique

in an airy tale of magical realism, Ibn Warraq brings a scholarly

sledge-hammer to the task of demolishing Islam. Writing a polemic

against Islam, especially for an author of Muslim birth, is an act

so incendiary that the author must write under a pseudonym; not to

do so would be an act of suicide.

And what does Ibn Warraq have to show for this act of unheard-of

defiance? A well-researched and quite brilliant, if somewhat

disorganized, indictment of one of the world's great religions.

While the author disclaims any pretence to originality, he has read

widely enough to write an essay that offers a startlingly novel

rendering of the faith he left.

To begin with, Ibn Warraq draws on current Western scholarship to

make the astonishing claim that Muhammad never existed, or if he

did, he had nothing to do with the Qur'an. Rather, that holy book

was fabricated a century or two later in Palestine, then "projected

back onto an invented Arabian point of origin." If the Qur'an is a

fraud, it's not surprising to learn that the author finds little

authentic in other parts of the Islamic tradition. For example, he

dispatches "The whole of Islamic law" as "a fantastic creation

founded on forgeries and pious fictions." The whole of Islam, in

short, he portrays as a concoction of lies.

Having thus dispensed with religion, Ibn Warraq takes up history and

culture. Turning political correctness exactly on its head, he

condemns the early Islamic conquests and condones European

colonialism. "Bowing toward Arabia five times a day," he writes,

referring to the Islamic prayer toward Mecca, "must surely be the

ultimate symbol of . . . cultural imperialism" In contrast, European

rule, "with all its shortcomings, ultimately benefited the ruled as

much as the rulers. Despite certain infamous incidents, the European

powers conducted themselves, on the whole, very humanely."

To the conventional argument that the achievements of Islamic

civilization in the medieval period shows the greatness of Islam,

Ibn Warraq revives the Victorian argument that Islamic civilization

came into existence not because of the Qur'an and Islamic law but

despite it. The stimulus in science and the arts came from outside

the Muslim world; where Islam reigned, these accomplishments took

place only where the dead hand of Islamic authority could be

avoided. Crediting Islam for the medieval cultural glories, he

believes, would be like crediting the Inquisition for Galileo's

discoveries.

Turning to the present, Ibn Warraq argues that Muslims have

experienced great travails trying to modernize because Islam stands

fore-square in their way. Its regressive orientation makes change

difficult: "All innovations are discouraged in Islam-every problem

is seen as a religious problem rather than a social or economic

one." This religion would seem to have nothing functional to offer.

"Islam, in particular political Islam, has totally failed to cope

with the modern world and all its attendant problems-social,

economic, and philosophical." Nor does the author hold out hope for

improvement. Take the matter of protecting individuals from the

state: "The major obstacle in Islam to any move toward international

human rights is God, or to put it more precisely . . . the reverence

for the sources, the Koran and the Sunna."

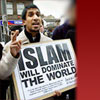

In a chapter of particular delicacy, given that he himself is a

Muslim living in the West, Ibn Warraq discusses Muslim emigration to

Europe and North America. He worries about the importation of

Islamic ways and advises the British not to make concessions to

immigrant demands but to stick firmly by their traditional

principles. "Unless great vigilance is exercised, we are all likely

to find British society greatly impoverished morally" by Muslim

influence. At the same time, as befits a liberal and

Western-oriented Muslim, Ibn Warraq argues that the key dividing

line is one of personal philosophy based and not (as Samuel

Huntington would have it) religious adherence. "[T]he final battle

will not necessarily be between Islam and the West, but between

those who value freedom and those who do not." This argument in fact

offers hope, implying as it does that peoples of divergent faiths

can find common ground.

As a whole, Ibn Warraq's assessment of Islam is exceptionally

severe: the religion is based on deception; it succeeded through

aggression and intimidation; it holds back progress; and it is a

"form of totalitarianism." Surveying nearly fourteen centuries of

history, he concludes, "the effects of the teachings of the Koran

have been a disaster for human reason and social, intellectual, and

moral progress."

As if this were not enough, Ibn Warraq tops off his blasphemy with

an assault on what he calls "monotheistic arrogance" and even

religion as such. He asks some interesting questions, the sort that

we in the West seem not to ask each other any more. "If there is a

natural evolution from polytheism to monotheism, then is there not a

natural development from monotheism to atheism?" Instead of God

appearing in obscure places and murky circumstances, "Why can He not

reveal Himself to the masses in a football stadium during the final

of the World Cup"? In 1917, rather than a miracle in Fatima,

Portugal, why did He not end the carnage on the Western Front?

This discussion points out just how much these issues are no longer

discussed in mainstream American intellectual life. Believers and

atheists go their separate ways, vilifying the other without

engaging in debate. For this reason, many of Ibn Warraq's

anti-religious statements have a surprisingly fresh quality.

It is hard for a non-Muslim fully to appreciate the offense Ibn

Warraq has committed, for his book of deep protest and astonishing

provocation goes beyond anything imaginable in our rough-and-tumble

culture. We have no pieties remotely comparable to Islam's. In the

religious realm, for example, Joseph Heller turned several Biblical

stories into pornographic fare in his 1984 novel God Knows, and no

one even noticed. For his portrayal of Jesus' sexual longings in the

1988 film The Last Temptation of Christ, Martin Scorsese faced a few

pickets but certainly no threats to his life. Rushdie himself has

recently raised hackles in India by making fun of Bal Thackeray, a

fundamentalist Hindu leader-yet no threats have come from that

quarter. In the political arena, Charles Murray and Dinesh D'Souza

published books on the very most delicate American topic, the issue

of differing racial abilities, and neither had to go into hiding as

a result.

In contrast, blasphemy against Islam leads to murder-and not just to

Salman Rushdie or in places like Egypt and Bangladesh. At least one

such execution has taken place on American soil. Rashad Khalifa, an

Egyptian biochemist living in Tucson, Arizona, analyzed the Qur'an

by computer and concluded from some rather complex numerology that

the final two verses of the ninth chapter do not belong in the holy

book. This insight eventually prompted him to declare himself a

prophet, a very serious offense in Islam (which holds Muhammad to be

the last of the prophets). Some months later, on 31 January 1990,

unknown assailants-presumably orthodox Muslims angered by his

teachings-stabbed Khalifa to death. While the case remains unsolved,

it sent a clear and chilling message: even in the United States,

deviancy leads to death.

Writers deemed unfriendly to Islam are murdered all the time. Dozens

of journalists have lost their lives in Algeria as well as prominent

writers in Egypt and Turkey. Taslima Nasrin had to flee her native

Bangladesh for this reason. A terrible silence has descended on the

Muslim world, so that a book of this sort can only be published in

the West.

In this context, Ibn Warraq's claim of the right to disagree with

Islamic tenets is a shock. And all the more so when he claims even

the Westerner's right to do so disrespectfully! "This book is first

and foremost an assertion of my right to criticize everything and

anything in Islam-even to blaspheme, to make errors, to satirize,

and mock." Why I Am Not a Muslim does have a mocking quality, to be

sure, but it is also a serious and thought-provoking book. It calls

not for a wall of silence, much less a Rushdie-like fatwa on the

author's life, but for an equally compelling response from a

believing Muslim.