Excerpts From Rushdie Address: 1,000 Days 'Trapped Inside a Metaphor'

20 Dec, 2006

Published on December 12, 1991in New York Times

Following are excerpts from a speech at Columbia University last

night by Salman Rushdie. The speech was adapted from a forthcoming

essay titled "One Thousand Days in a Balloon":

A hot-air balloon drifts slowly over a bottomless chasm, carrying

several passengers. A leak develops. . . . The wounded balloon can

bear just one passenger to safety. . . . But who should live, who

should die? And who could make such a choice?

In point of fact, debating societies everywhere regularly make such

choices without qualms, because of course what I've described is the

given situation of that evergreen favorite, the Balloon Debate, in

which, as the speakers argue over the relative merits and demerits

of the well-known figures they have placed in disaster's mouth, the

assembled company blithely accepts the faintly unpleasant idea that

a human being's right to life is increased or diminished by his or

her virtues or vices -- that we may be born equal but thereafter our

lives weigh very differently in the scales.

. . .

I have now spent over a thousand days in just such a balloon; but,

alas, this isn't a game. For most of these thousand days, my

fellow-travelers included the Western hostages in Lebanon, and the

British businessmen imprisoned in Iran and Iraq, Roger Cooper and

Ian Richter. And I had to accept, and did accept, that for most of

my countrymen and countrywomen, my plight counted for less than the

others'. In any choice between us, I'd have been the first to be

pitched out of the basket and into the abyss. "Our lives teach us

who we are," I wrote at the end of my essay "In Good Faith." Some of

the lessons have been harsh, and difficult to learn.

Trapped inside a metaphor, I've often felt the need to redescribe

it, to change the terms. This isn't so much a balloon, I've wanted

to say, as a bubble, within which I'm simultaneously exposed and

sealed off. The bubble floats above and through the world, depriving

me of reality, reducing me to an abstraction. For many people, I've

ceased to be a human being. I've become an issue, a bother, an

"affair." . . . And has it really been so long since religions

persecuted people, burning them as heretics, drowning them as

witches, that you can't recognize religious persecution when you see

it? . . .

What is my single life worth? Despair whispers in my ear: "Not a

lot." But I refuse to give in to despair . . . because . . . I know

that many people do care, and are appalled by the . . . upside-down

logic of the post- fatwa world, in which a . . . novelist can be

accused of having savaged or "mugged" a whole community, becoming

its tormentor (instead of its . . . victim) and the scapegoat for .

. . its discontents. . . . (What minority is smaller and weaker than

a minority of one?)

I refuse to give in to despair even though, for a thousand days and

more, I've been put through a degree course in worthlessness, my own

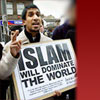

personal and specific worthlessness. My first teachers were the mobs

marching down distant boulevards, baying for my blood, and finding,

soon enough, their echoes on English streets. . . . At first, as I

watched the marchers, I felt them trampling on my heart.

. . .

Sometimes I think that one day, Muslims will be ashamed of what

Muslims did in these times, will find the "Rushdie affair" as

improbable as the West now finds martyr-burning. One day they may

agree that -- as the European Enlightenment demonstrated -- freedom

of thought is precisely freedom from religious control, freedom from

accusations of blasphemy. Maybe they'll agree, too, that the row

over "The Satanic Verses" was at bottom an argument about who should

have power over the grand narrative, the Story of Islam, and that

that power must belong equally to everyone. That even if my novel

were incompetent, its attempt to retell the story would still be

important. That if I've failed, others must succeed, because those

who do not have power over the story that dominates their lives,

power to retell it, rethink it, deconstruct it, joke about it, and

change it as times change, truly are powerless, because they cannot

think new thoughts.

One day. Maybe. But not today.

. . .

Back in the balloon, something longed-for and heartening has

happened. On this occasion, mirabile dictu, the many have not been

sacrificed, but saved. That is to say, my companions, the Western

hostages and the jailed businessmen, have by good fortune and the

efforts of others managed to descend safely to earth, and have been

reunited with their . . . own, free lives. I rejoice for them, and

admire their courage, their resilience. And now I'm alone in the

balloon.

Surely I'll be safe now? Surely . . . the balloon will drop safely

towards some nearby haven? . . . Surely it's my turn now?

But the balloon is . . . still sinking. I realize that it's carrying

a great deal of valuable freight. Trading relations, armaments

deals, the balance of power in the Gulf -- these and other matters .

. . are weighing it down. . . . I hear voices suggesting that if I

stay aboard, this precious cargo will be endangered. The national

interest is being redefined; am I being redefined out of it? Am I to

be jettisoned from the balloon, after all?

When Britain renewed relations with Iran at the United Nations in

1990, . . . British officials . . . assured me unambiguously that

something very substantial had been achieved on my behalf. The

Iranians . . . had secretly agreed to forget the fatwa. . . . They

would "neither encourage nor allow" their citizens, surrogates or

proxies to act against me. Oh, how I wanted to believe that! But in

the year-and-a-bit that followed, we saw the fatwa restated in Iran,

the bounty money doubled, the book's Italian translator severely

wounded, its Japanese translator stabbed to death; there was news of

an attempt to find and kill me by contract killers working directly

for the Iranian Government. . . .

It seems reasonable to deduce that the secret deal made at the

United Nations hasn't worked. Dismayingly, however, the talk as I

write is all of improving relations with Iran still further. . . .

Is this a balloon I'm in, or the dustbin of history?

Let me be clear: There is nothing I can do to break this impasse.

The fatwa was politically motivated to begin with, it remains a

breach of international law, and it can only be solved at the

political level. To effect the release of the Western hostages in

Lebanon, great levers were moved . . . for the businessman Mr.

Richter, 70 million pounds in frozen Iraqi assets were "thawed."

What, then, is a novelist under terrorist attack worth?

Despair murmurs, once again: "Not a plugged nickel."

But I refuse to give in to despair.

You may ask why I'm so sure there's nothing I can do to help myself.

. . .

At the end of 1990, dispirited and demoralized . . . I faced my

deepest grief, my . . . sorrow at having been torn away from . . .

the cultures and societies from which I'd always drawn my . . .

inspiration -- that is, the broad community of British Asians . . .

the broader community of Indian Muslims. I determined to make my

peace with Islam, even at the cost of my pride. Those who were

surprised and displeased by what I did perhaps failed to see that .

. . I wanted to make peace between the warring halves of the world,

which were also the warring halves of my soul. . . .

The really important conversations I had in this period were with

myself.

I said: Salman, you must send a message loud enough to . . . make

ordinary Muslims see that you aren't their enemy, and you must make

the West understand a little more of the complexity of Muslim

culture . . ., and start thinking a little less stereotypically. . .

. And I said to myself: Admit it, Salman, the Story of Islam has a

deeper meaning for you than any of the other grand narratives. Of

course you're no mystic, mister. . . . No supernaturalism, no

literalist orthodoxies . . . for you. But Islam doesn't have to mean

blind faith. It can mean what it always meant in your family, a

culture, a civilization, as open-minded as your grandfather was, as

delightedly disputatious as your father was. . . . Don't let the

zealots make Muslim a terrifying word, I urged myself; remember when

it meant family . . . .

I reminded myself that I had always argued that it was necessary to

develop the nascent concept of the "secular Muslim," who, like the

secular Jew, affirmed his membership of the culture while being

separate from the theology. . . . But, Salman, I told myself, you

can't argue from outside the debating chamber. You've got to cross

the threshold, go inside the room, and then fight for your

humanized, historicized, secularized way of being a Muslim. . . .

It was with such things in mind -- and with my thoughts in a state

of some confusion and torment -- that I spoke the Muslim creed

before witnesses. But my fantasy of joining the fight for the

modernization of Muslim thought . . . was stillborn. It never really

had a chance. Too many people had spent too long demonizing or

totemizing me to listen seriously to what I had to say. In the West,

some "friends" turned against me, calling me by yet another set of

insulting names. Now I was spineless, pathetic, debased; I had

betrayed myself, my Cause; above all, I had betrayed them .

I also found myself up against the granite, heartless certainties of

Actually Existing Islam, by which I mean the political and priestly

power structure that presently dominates and stifles Muslim

societies. Actually Existing Islam has failed to create a free

society anywhere on Earth, and it wasn't about to let me, of all

people, argue in favor of one. Suddenly I was (metaphorically) among

people whose social attitudes I'd fought all my life -- for example,

their attitudes about women (one Islamicist boasted to me that his

wife would cut his toenails while he made telephone calls, and

suggested I find such a spouse) or about gays (one of the Imams I

met in December 1990 was on TV soon afterwards, denouncing Muslim

gays as sick creatures who brought shame on their families and who

ought to seek medical and psychiatric help). . . .

I reluctantly concluded that there was no way for me to help bring

into being the Muslim culture I'd dreamed of, the progressive,

irreverent, skeptical, argumentative, playful and unafraid culture

which is what I've always understood as freedom. . . . Actually

Existing Islam . . . which makes literalism a weapon and

redescription a crime, will never let the likes of me in.

Ibn Rushd's ideas were silenced in their time. And throughout the

Muslim world today, progressive ideas are in retreat. Actually

Existing Islam reigns supreme, and just as the recently destroyed

"Actually Existing Socialism" of the Soviet terror-state was

horrifically unlike the utopia of peace and equality of which

democratic socialists have dreamed, so also is Actually Existing

Islam a force to which I have never given in, to which I cannot

submit.

There is a point beyond which conciliation looks like capitulation.

I do not believe I passed that point, but others have thought

otherwise.

I have never disowned "The Satanic Verses", nor regretted writing

it. I said I was sorry to have offended people, because I had not

set out to do so, and so I am. I explained that writers do not agree

with every word spoken by every character they create -- a truism in

the world of books, but a continuing mystery to "The Satanic Verses'

" opponents. I have always said that this novel has been traduced.

Indeed, the chief benefit to my mind of my meeting with the six

Islamic scholars on Christmas Eve 1990 was that they agreed that the

novel had no insulting motives. "In Islam, it is a man's intention

that counts," I was told. "Now we will launch a worldwide campaign

on your behalf to explain that there has been a great mistake." All

this with much smiling and friendliness. . . . It was in this

context that I agreed to suspend -- not cancel -- a paperback

edition, to create what I called a space for reconciliation.

Alas, I overestimated these men. Within days, all but one of them

had broken their promises, and recommenced to vilify me and my work

as if we had not shaken hands. I felt (most probably I had been) a

great fool. The suspension of the paperback began at once to look

like a surrender. In the aftermath of the attacks on my translators,

it looks even worse. It has now been more than three years since

"The Satanic Verses" was published; that's a long, long "space for

reconciliation." It is long enough. I accept that I was wrong to

have given way on this point. "The Satanic Verses" must be freely

available and easily affordable, if only because if it is not read

and studied, then these years will have no meaning. Those who forget

the past are condemned to repeat it.

"Our lives teach us who we are." I have learned the hard way that

when you permit anyone else's description of reality to supplant

your own -- and such descriptions have been raining down on me, from

security advisers, governments, journalists, Archbishops, friends,

enemies, mullahs -- then you might as well be dead. Obviously, a

rigid, blinkered, absolutist world view is the easiest to keep hold

of, whereas the fluid, uncertain, metamorphic picture I've always

carried about is rather more vulnerable. Yet I must cling with all

my might to . . . my own soul; must hold on to its mischievous,

iconoclastic, out-of-step clown-instincts, no matter how great the

storm. And if that plunges me into contradiction and paradox, so be

it; I've lived in that messy ocean all my life. I've fished in it

for my art. This turbulent sea was the sea outside my bedroom window

in Bombay. It is the sea by which I was born, and which I carry

within me wherever I go.

"Free speech is a non-starter," says one of my Islamic extremist

opponents. No, sir, it is not. Free speech is the whole thing, the

whole ball game. Free speech is life itself.

. . .

What is my single life worth?

Is it worth more or less than the fat contracts and political

treaties that are in here with me? Is it worth more or less than

good relations with a country which, in April 1991, gave 800 women

74 lashes each for not wearing a veil; in which the 80-year-old

writer Mariam Firouz is still in jail, and has been tortured; and

whose Foreign Minister says, in response to criticism of his

country's lamentable human rights record, "International monitoring

of the human rights situation in Iran should not continue

indefinitely . . . Iran could not tolerate such monitoring for

long"?

You must decide what you think a friend is worth to his friends,

what you think a son is worth to his mother, or a father to his son.

You must decide what a man's conscience and heart and soul are

worth. You must decide what you think a writer is worth, what value

you place on a maker of stories, and an arguer with the world.

Ladies and gentlemen, the balloon is sinking into the abyss.