The Islamic concept of Just War (aka Jihad), and why there is always a pssibility that a Muslim warm up to it and commit massacre as did Major Nidal Malik Hasan at Fort Hood, Texas.

It's not every day that religion appears as a front page story in today's newspapers the world over, particularly on a regular basis! But over the past 20 years, one religion has really made to the front pages, perhaps, more often than any other news… it is terrorist activities—the religion of Islam portrays. In this essay, I dig into WHY THIS HAPPENS.

Islam claims more than one billion followers worldwide. It is the fastest growing religion in the world; and it influence touches virtually every area of life of the Muslim faithful: not only the spiritual, but also the political and economic. What is more, its influence is being felt closer and closer to home here in the United States. There are now up to 5 million Muslims in the U.S., and over 1,100 mosques or Islamic centers (estimated figures).

What does Islam really teach? How are these teachings of Islam similar to those of Christianity, the dominant religion in the U.S.? How are these beliefs different? What should our attitudes be toward Islam and towards those, who follow this powerful religion? Well, these are some of the questions/issues that I want to address in this essay.

In February 1998, long before the 9/11 terrorist attacks on American soil, Osama bin Laden and four other leaders of radical Islamist groups in various countries issued a fatwa or an Islamic religious ruling, calling for jihad against “the Crusader-Zionist alliance” in the following language:

“In compliance with Allah’s orders, we issue the following fatwa to all Muslims: the ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it, in order to liberate the al-Aqsa Mosque [Jerusalem] and the holy mosque [Mecca] from their grips, and in order for their armies to move out of the holy lands of Islam… This is in accordance with the words of the true Almighty Allah, and fight the pagans all together as they fight you all together and fight them until there is no more tumult or oppression, and there prevail Islamic justice and faith in Allah.”

Bombing of USS Cole in Yemeni port of Aden by al-Qaeda on October 12, 2000 that killed 17 US saidlors. |

While more examples of Osama’s thinking emerged after the 9/11 attacks, this fatwa stands as a fundamental statement of his rationale for a campaign of violence against America and the West: an appeal to the Islamic tradition of defensive jihad by which every Muslim is obligated; as an individual’s duty, to take up arms against such invaders of Islamic lands. It lays out their justifications, not only for these attacks of 9/11, but also for other terrorist attacks linked to his al-Qaeda group, notably, the bombings of the two American Embassies in East Africa (Kenya and Tanzania) in August 1998 and of the U.S.S. Cole in October 2000. It also serves as a warrant for future such attacks by “every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it”—i.e. for a continuing war by terrorist and other means by Muslims against “Americans and their allies”, an ongoing clash of civilizations.

How should this call to perpetual Jihad be understood in relation to such Islamic traditions? And, how does it compare to the just war tradition of Western culture?

The classical Islamic conceptions of Islamic Jihad, in the sense of warfare, comes not from the holy Qur’an directly, where the term jihad is used in reference to the believer’s inner struggles for righteousness, but from the jurists of the early Abbasid periods (the late eighth and early ninth centuries C.E.), who developed it in the contexts of a general effort to clarify the nature of the Islamic communities at large—proper leadership of that Muslim community and their relations with the non-Islamic world. Central to these concepts is a legal division of the world into two realms: the dar al-Islam or the abode of Islam, and the remainder of the world, defined as the dar al-harb or abode of war.

|

|

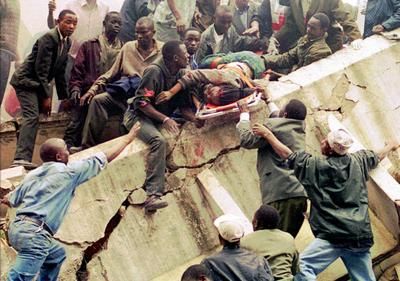

| On Aug 7, 1998, an al-Qaeda suicide-bomber struck the U.S. Embassy in Kenya, killing 213 people (12 Americans), and wounding more than 4,500. |

Four minutes after the Kenya attack, another suicide car-bomber attacked the U.S. Embassy in Tanzania, killing 11 and injuring 85. |

The dar al-Islam, as the jurists understood it, had existed since its creation by the Prophet Muhammad himself, the holy messenger of Allah, who had been its first head. It was a community, both religious and political, and thus its ruler, namely the Prophet, was understood to be supreme in both spheres. There could be only one right ruler at a time, understood to be the successor of the Prophet and inheritor of his authority. Because of its characters—namely its essential unity, its rule by a successor of the Prophet, its governance according to divine Islamic laws—the dar al-Islam is fundamentally different from the rest of the world (dar al-harb). Dar al-harb is seen as perpetual threat, real or imagined, to dar al-Islam; therefore, the Muslim world must remain engaged is a perpetual conflicts with the infidel world. As a result, a general, lasting and universal peace is impossible until the dar al-harb is no more, when the whole world has become the dar al-Islam, a place within which submission (Islam) to Allah is the law of the land. Until then, war between the two realms is the normal state in Islamic belief systems. Yet, at the same time, Muslims are permitted to create extended periods of peace by means of false or tactical treaties between the dar al-Islam and the non-Islamic societies—a tactic the Prophet repeatedly used against his infidels neighbors and opponents.

This conception formed the background for the Islamic jurists, conception of the idea of jihad as warfare. As they described it, this warfare could take two forms: that of the dar al-Islam as a body under the authority of its legitimate ruler, the caliph for the Sunni traditions, and the imam for the Shiites—a conception that encompassed offensive wars imagined threats from a perceived enemy (dar al-harb), as well as defensive jihad, namely an organized collective defense against direct attacks on the dar al-Islam by a force from some part of the dar al-harb.

In the former case, the duty to take part in Islamic Jihads was conceived as a collective effort, with some Muslims fighting, while others playing other roles, including simply going about their normal lives of ignorance; in the latter case, though, to fight was an individual duty, incumbent on all Muslims who were able to do so in the immediate area of the aggressions.

These were significantly different forms of warfare. The collective jihads was a thoroughly rule-governed activities, from the requirements of the caliph’s/imam’s authority to that of a declaration of hostilities and a call for peace to a form of combatant -noncombatant distinction to extensive discussion of the disposition of spoils by the ruling authority. The jurists clearly understood this as the norm for the warfare of the dar al-Islam. This form of jihad drew upon the religious unity of the Islamic communities even as it depended on the social and institutional relationships that comprised the Islamic states. The proper exercise of Islamic Jihad on this model strengthened dar al-Islam and the role of its rulers, both religiously and politically.

The jihad of emergency defense was another matter entirely. It assumed an acute emergency, in which normal religiously and socially prescribed relationships and structures were totally erased. This model of the jurists, who had it in mind, was simple: a direct attack upon dar al-Islam by a force from the dar al-harb in some particular places remote from the dar al-Islam’s center of authority and power. Against this attack, the Muslims in the area were to rise up in arms, on their own authorities, as a kind of levée en masse. The individual duty of Muslims is to take up arms crossed all the usual divisions: not only healthy men of fighting age but also women, children, the aged and the infirm were to fight to the limit of their abilities. Correspondingly, the rules of engagements of collective Islamic Jihads—wherein noncombatants weren’t present, therefore, playing no part in the conflict—did not apply. While Islamic jurists admitted this form of jihad in times of dire emergency caused by overt aggression of the enemy, there was an inherent tension between it and the collective jihad of the dar al-Islam under the authority of the caliph/imam. In practical terms, local leaders on the frontiers might (and did) use the excuse of the Islamic Jihad of emergency to challenge the legitimacy of the central authorities in Islam. However, this form of jihad(s) was originally meant to be an exceptional response to an exceptional circumstance, not the norms for Muslim warfare.

Islamic Jihadis on the march. |

It is generally agreed within Islam that the collective Jihad is impossible today, as there is no central caliph or imam now. This, itself, gives new importance to what was originally considered to be an exceptional case: the idea of defensive Islamic Jihad as an individual duty in the face of external aggressions. In the Islamic mainstream, this conception has developed along the lines compatible with the international laws to allow Muslim heads of state to organize and execute defense collectively; though on the juristic model they do so on the basis of the individual’s responsibilities of all their people to respond to such aggressions. The historical model for such actions, is the medieval hero Salahuddin Ayubi (Saladin), who, though only a regional commander (not the caliph), organized and led a successful defense against the armies of the second Crusades. In theory, this mainstream conception of defense respects the patterns of relationships within the society as well as the limits to be observed in fighting, the most important of which are understood to come from Prophet Muhammad himself.

However, over the last hundred years or so, we have seen the developments of another line of interpretations of the Islamic Jihads. Firstly, appearing in Northern Africa as an ideology for resistance against colonialism; by the 1960s, it was being used as the Islamic justifications for religious terrorist attacks against Israel, and in the 1970s and 1980s it was adapted to justify Islamic armed struggles by terror and assassinations in such states as Iran, Egypt, and Algeria, against the rulers who were nominally Muslims and were judged to be tools of Western imperialism. It is out of these traditions that Osama bin Laden’s fatwa has emerged.

These true (radical) forms of the Islamic Jihads, make several critical assumptions not found in the Islamic traditional conceptions or in the mainstream Islamic theories. Firstly, the dar al-Islam is conceived as ‘any territory whose population is mainly Muslim and which was once a part of the historical dar al-Islam.’ By this reasoning any non-Islamic state(s) existing within the territories of the historical dar al-Islam, as well as all non-Islamic presence within that space, must be resisted and subdued or eliminated completely. Furthermore, the “aggressors” are deemed to be all those, who support such states or non-Islamic presence/ideologies, so that the usual lines of distinctions between combatants and noncombatants are to be erased/eradicated, with the results that all individuals are considered as acceptable targets. Moreover, because of its origins in an “emergency”, there are no limits on the means in these struggles. Finally, all Muslims are faced with the duty to take part in these struggles or Islamic Jihads, so that it ultimately becomes one’s involving individuals rather than politically organized communities; anyone who accepts this duty—men of fighting age, women, children, and even the aged or infirm—becomes a combatant in these wars.

This extreme interpretations of such ideas of defensive Islamic Jihads, implicitly rejects much of the actual history of such Muslim societies and of their Muslim faiths. It leaves scant room for toleration of “people of the book”, as prescribed in the holy Quran, because it treats the simple presence of Christians and Jews in dominantly Muslim lands/societies as an act of aggression(s). It also leaves no room for differences of interpretations as to what Islam really requires; its reading of the Islamic law is very narrow and unyielding on these doctrines and such behaviors alike. So, social developments identified with modernity are rejected as un-Islamic, even if large numbers of Muslims have accepted them without losing their faiths in Allah…

Osama Bin Laden’s fatwa reflects all these assumptions. The United States is deemed as an able aggressor against all of Islam, because of the presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Afghanistan, despite the fact that they are there by agreement and that their purpose is to protect the Saudi, Iraqi and Afghan people from Islamic extremists and aggressive (Muslim) neighbors, not to dominate it. Likewise, the “protracted blockades” against Iraq is viewed as an assault on the Iraqi people, despite the fact that Saddam Hussein’s diversion of its rich resources for his own purposes is the real cause of Iraqi sufferings. The same could be said of Osama bin Laden’s hostility toward the U.S. support for “the Jews’ petty state” and “its occupation of Jerusalem and the murder of Muslims”. In other words, the United States has become the embodiment of the dar al–harb par excellence, engaged in aggressions against Islam, despite the fact that millions of Muslims live and enjoy religious freedom within the U.S. border. But Osama bin Laden’s fatwa takes the radical line of Islamic Jihad to new extremes, when it calls upon all Muslims to kill any and all Americans—“civilians and military” alike—“in any country in which it is possible to do it”. It is no longer a defensive war, but Islamic Jihad on its true offensive!

Osama and his associates, who formulated the fatwa, of course lack the religiously mandated authority to wage collective [offensive] Islamic Jihad, as they do not bear the mantle of succession to the Prophet of Islam. That is why they try to describe the war against America as a defensive one.

By painting the entire nation of America as guilty of “aggressions”, the fatwa can set aside such limits imposed on warfare by normative Islamic tradition. This includes no direct, intended killings of noncombatants and no use of fire (which is totally prohibited among Muslims because it is the weapon Allah will use in hell). Osama bin Laden’s Islamic Jihad or the Just War, not only pits Islam against America and the West as a whole, but ultimately to the rest of the non-Islamic world at large. It also seeks to overthrow contemporary Muslim states and their mainstream views of Islamic traditions among the great majority of contemporary moderate Muslims.

To be sure, like Osama bin Laden, the early Islamic jurists of the Abbasid period also thought that the relationships between the Islamic and non-Islamic worlds to be one of perpetual conflicts, and their Islamic notions of collective Jihad reflects the Islamic aim of eventual submission (Islam) of the entire world to Allah. Yet they never defined these eschatological goals as the one that could be achieved only by wars or even primarily by wars... And in the absence of any universal Muslim ruler, bearing the mantle of authority of the Prophet, the Muslim traditions and the Muslim way of life have found ways of pursuing these goals by other nonmilitary means. The radical ideology of Islamic Jihad changes all this by making the use of such violent, terrorist means indiscriminately and without principled limits, a binding obligation for all Muslims.

The idea of ‘Just War’ is also deeply rooted in Western tradition; it is, perhaps, more strongly institutionalized in today’s international law, in American military doctrines and practices, and even in political cultures since the Victorian Age! Though the Islamic Jihad or ‘Just War’ tradition has important Christian roots, it differs from the Islamic juristic traditions in that it can be employed without explicitly religious premises. Similarly, in Western political thoughts and theology, more generally, the nature of the political community, the role of the government and the use of armed forces are conceived in secular, not religious terms. All these features differentiate the Islamic Jihad or ‘Just War’ traditions from the Western ‘Just War’ concept; in Islamic Juristic traditions, Islamic Jihad must be commanded by a pious caliph/imam and is always directed against dar al-hard.

|

Jihad, Hatred & Major Nidal Hasan |

Yet, there are also significant points of contact, which reveal important common interests. I have already suggested this by noting that the mainstream Islamic thoughts and political practices have developed a way, compatible with the international laws, and orderly peaceful interactions with non-Muslim nations. More specifically, both such traditions link the rights to use the force of arms to the exercise of legitimate governing authorities for the protection and of the common good of the Islamic communities. Such common good, moreover, is defined normatively in terms of high ideals of values and behaviors, not in terms of repressions and intolerance. Both Islamic traditions recognizes that even the use of force justified in this way is not without limits, when it comes to the questions of who may be targeted and the means that may be used against the aggressors. These are all matters on which there can and should be a pursuit of common causes. The radical Islamic doctrines of jihad, advanced as the justifications for contemporary terrorism, is a challenge to both of these traditions, and people of goodwill from both communities have reasons to reject it!

So, the reason behind the present killing at Fort Hood Army base at Texas by the lone Islamic crusader, ‘hate doctor’ Major Nidal Malik Hassan, is this Islamic doctrine of Jihad, or Islamic Just War, which is one of the Pillars of Islam. We need to understand this conclusively, that every Muslim, whether moderate or extremist, are indeed sleepwalkers and can wake up on any given day to strike terror into our hearts!

Comments powered by CComment